A Talk with Barbara Smith

by k.e. harloe

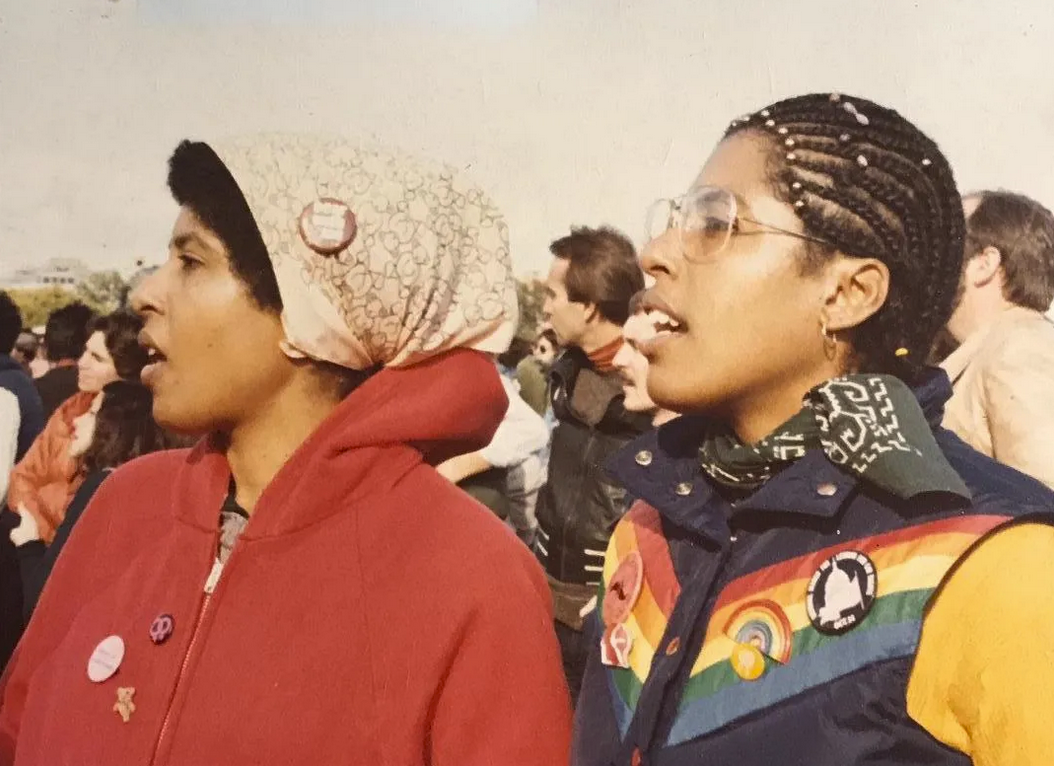

It's hard to know where to start an introduction for Barbara Smith. A renowned Black feminist scholar, lecturer, writer, activist, publisher, and organizer, Smith, alongside other Black feminists including Beverly Smith and Demita Frazier, formed the Combahee River Collective (CRC) in 1974. Three years later, Smith co-authored the Combahee River Collective Statement, a manifesto widely believed to contain the first use of the term “identity politics.”

In 1980, Audre Lorde called Smith and said, “we really need to do something about publishing.” This conversation gave birth to the Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, which Smith was involved with for 15 years, publishing revolutionary texts including Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa’s This Bridge Called My Back and Lorde’s Apartheid U.S.A. Alongside this work, Smith also taught Black women’s literature, and continued organizing. In 2005, she was elected to Albany, New York’s Common Council (i.e., City Council).

I know Smith not only through her work, but also as a comrade, friend and neighbor in Albany. She is a charter member of the Albany Justice Coalition (AJC), a grassroots group that’s scored important local policy victories and accountability measures. She’s also an active member of the national Ukraine Solidarity Network (USN), as well as Ukraine Solidarity Capital District, and a very active member of the Albany chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP). This fall, she helped lead a grassroots effort to push Albany’s Common Council to introduce and pass the first Gaza ceasefire resolution in the state of New York. She is, in other words, the real deal—forgoing a relaxed retirement for the hard daily work of hyper-local organizing.

I got together with Smith to talk about Palestine, local and international organizing, and the role of media in the movement for liberation. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Smith and I spoke two weeks before January 4, when Albany’s Common Council passed the ceasefire resolution we discuss below.

k.e. harloe: How did you first come to a politics and understanding around Palestine?

Barbara Smith: I was very much involved in the movement to end the war in Vietnam. When I went to college in 1965, there was not a widespread anti-war movement. Before college, I had a high school AP European History teacher who had the most significant impact on me, perhaps in my entire life. He loved my twin sister and me, and we loved him. He had been in the army during Korea.

I went to college with his perspective on the war in Vietnam, which was that this was a just war, no questions. When I met some of the leftist student leaders at Mount Holyoke, I began to see the war another way. There were few Black students—15—in my 400-person class. It was like a little tiny Norman Rockwell town: There were no Black people in the town, and the one Black professor could not buy a house in the town. That was South Hadley. Mount Holyoke was an extremely elite college back then, because women could not go to the Ivy League; a lot of people who would've been at an Ivy League school were at the Seven Sisters.

From that day to this, I've always paid attention to what is going on internationally. I was involved in the Central America Solidarity Movement in the 1980s, and in speaking out and opposing apartheid in South Africa. When I moved to Albany, I went to many protests organized by the Palestine Rights Committee. That to me is just the basic work of being an alert organizer and activist with the kind of politics that I have, which I consider to be an international Black feminist perspective.

We are in a crisis situation, and one of my issues is that I don’t drop organizing; I keep up with the Albany Justice Coalition and Ukraine Solidarity Capital District and the national Ukraine Solidarity Network, and this fall I became active in Black4Palestine, and the revived [Albany] JVP chapter—though I’ve been a member of JVP since 2018.

I'm not an expert in the geopolitical or political history of what we’re discussing. That's not my expertise. My expertise—I'll talk about African-American literature and African-American studies until the cows come home. But I do know right from wrong. That's a good thing to know: right from wrong, and what it means to stand on the side of justice.

I am also a person of color living in the United States—a Black, African-American person specifically. My roots are in a couple of countries, but some of the roots that are the most defining of my experience living here are my roots in Africa. Those roots are directly tied to the slave trade and to chattel slavery in the United States, and this really formed my social and political identity. As a person of color living in the United States, I mean, it's obvious what's happening [in Gaza]. I don't have to wonder, like, "How did that happen? Why did that happen?" These are status quo relationships of colonialism, power, racial superiority, and dominance. There's a history of solidarity between people of African heritage and Palestinians.

harloe: I’m curious how you’ve experienced this time since October 7th—what you’re experiencing or seeing in this moment.

Smith: I've experienced it as a complete nightmare; how do I say it? It is like a tiny speck compared to what people on the ground in Palestine are experiencing. It's unspeakable.

harloe: You and I have been fortunate to be a part of a small coalition of organizers who came together to develop—and push Albany’s Common Council to pass—a ceasefire resolution. I want to ask you about this because the local, on-the-ground organizing we’ve been involved in is remarkable, and it is one of the places where I personally have found the closest thing to hope.

Smith: I'm very happy to talk about that because it is so uplifting.

harloe: If you're only reading about the movement for Palestinian liberation or the anti-Zionist movement from a distance, you might not understand how much solidarity there actually is on the ground. I have felt a pretty big contrast between how I see these movements described—or argued about—on social media, or in mainstream news outlets, versus what I experience when I go to a protest or a meeting. I know we both have been moved by the solidarity we’ve experienced in person. When I physically show up to these spaces, I have only experienced support and solidarity as a Jewish person.

Smith: The Common Council meeting we attended on December 18 was one of the most remarkable experiences I have ever had in the context of organizing. The solidarity and love were just beautiful!

harloe: A little background: The group we’ve been involved with for the local ceasefire resolution includes members of Albany’s Muslim, Palestinian, and Arab communities, as well as members of the local JVP chapter—including people who are Jewish, Israeli, or Black. The first version of the resolution was submitted at a Common Council meeting on December 4th, and many of us showed up to give public comments. Shortly after that meeting, higher-ups at the Common Council threatened to not even let the resolution be introduced, let alone come to a vote.

Organizers within our group raised money to purchase a full page ad in the Times Union, which we then had 19 organizations co-sign, including the local branch of the NAACP, the local Working Families Party, local mosques, labor groups and unions, and others.

Smith: People came out in force. Early on I said, people are expecting us to come and do public comment at City Hall. But we have to do some things that they're not expecting. Like the vigil we held outside the council meeting. Like the full-page newspaper ad.

We didn't ever have a conversation like, how do you think the ad went for us? Well, it was kind of obvious because people were standing around the City Council chamber holding up the ad. I had no idea how much media was there. I had no idea the Times Union was there. I had no idea WAMC was there. Channel 6 called me as I was trying to get downtown.

One of the reasons I love media coverage like this so much is that getting media attention for your progressive slash leftist, queer, feminist, people of color organizing is like putting one over on the man, because the man doesn't want anybody to know any of this. So every time I can get a media hit, I'm like, Yeah—see what happened there?

And now, they are trying to shut Black studies down, women's studies, queer studies. Critical race theory. They're trying to shut the whole thing down. I say to people: Do you see how successful we've been? The ignorant, narrow, and vicious white right wing—they see that young people’s minds are changing. Most young people want Palestine to be free. They say, no, no, no. We can't have people getting this kind of information.

Too late. Too late. The genie is out of the bottle. The stuff exists.

And I don't like the fact that, in particular, African American studies is under attack, because that's my jam. That's not what I'm saying at all. Though I do know why it's under attack. It's because it's been very effective in changing consciousness, and opening up worlds to people.

Why shouldn't people read Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, and not just Faulkner and Hemingway? Why can't that be the case? That's what we built.

But I digress as always. That's why I said I can never do a short interview.

harloe: The work never stops.

Smith: It doesn't. No. Because the systems don't stop. We haven't smashed them yet.

After 9/11, we started the Stand for Peace Anti-Racism Committee (SPARC), an offshoot of a peace group specifically focused on stopping the war in Iraq. SPARC decided that our major focus would be building connections with people in the Muslim and Arab-American community,particularly women, because we were all women in our group. We would go out and have meals together every so often. It was always so remarkable—to be with people, backgrounds of all kinds. It was what life is supposed to be. And then, guess who I saw when I was at City Hall [to speak in support of the ceasefire resolution] on December the 4th]?

harloe: Who?

Smith: One of the people who had been a leader in our old group. We saw each other after the public comment period. She was so happy to see me, and I was so happy to see her. I said, “We've been doing this for a long time, haven't we?”